Like Julie and Julia. (2009 Nora Ephron). Sort of. You know, the movie, where the girl in the tiny New York apartment took a year and made it her mission to recreate each one of the 524 recipes in Julia Child’s book “Mastering the Art of French Cooking”.

Julie Powell actually started the Julie/Julia project on her blog and garnered the attention of quite a few followers, including those who offered her a book deal at Little, Brown and Company. Julia Child was reportedly unimpressed and said as much, although I think that was a little hoity-toity of her. The book led to the movie and the rest, as they say, is history.

But get to the point Carol. Your idea?

One of my first poet loves was Emily Dickinson and the very first poem I memorized was:

I‘m nobody.

Who are you?

Are you nobody too?

Then there’s a pair of us- don’t tell!

They’d banish us you know.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog .

To tell your name the lifelong day

To an admiring bog!”

At 10, just as now, this particular poem seemed perfectly suited for my introverted self.

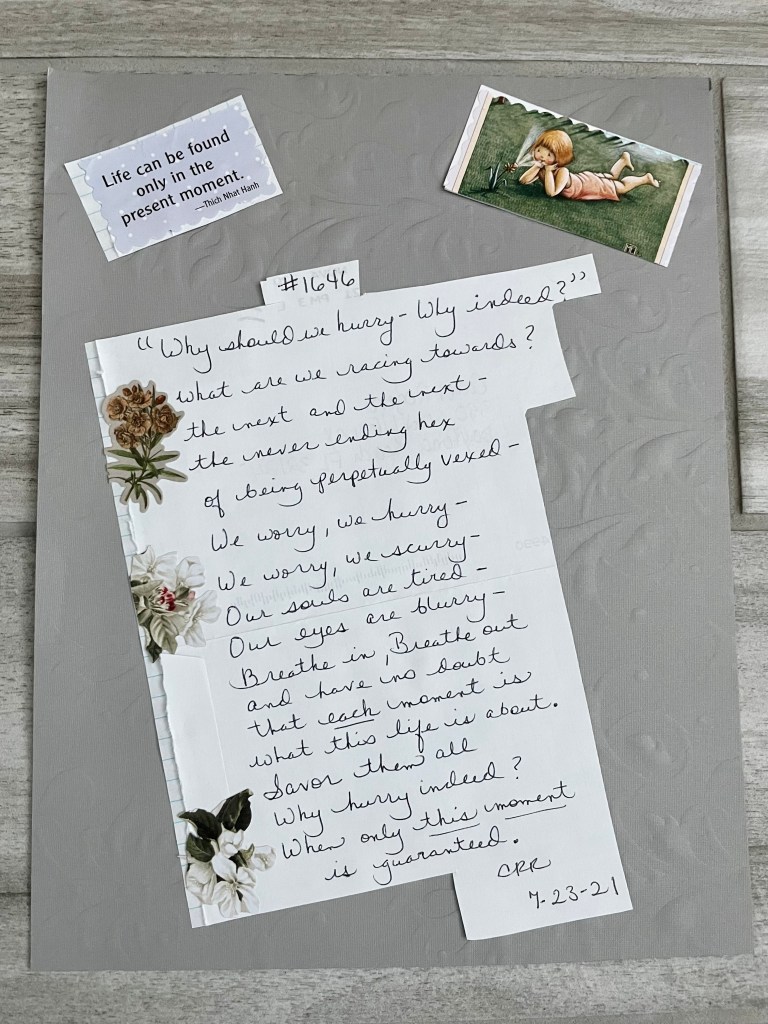

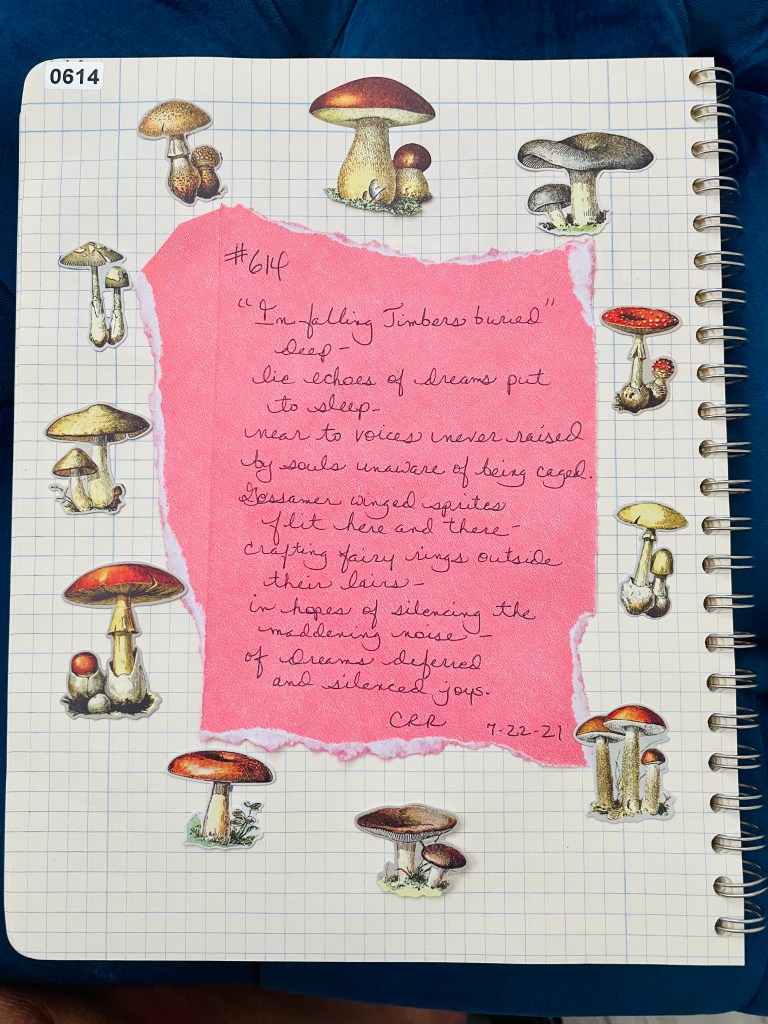

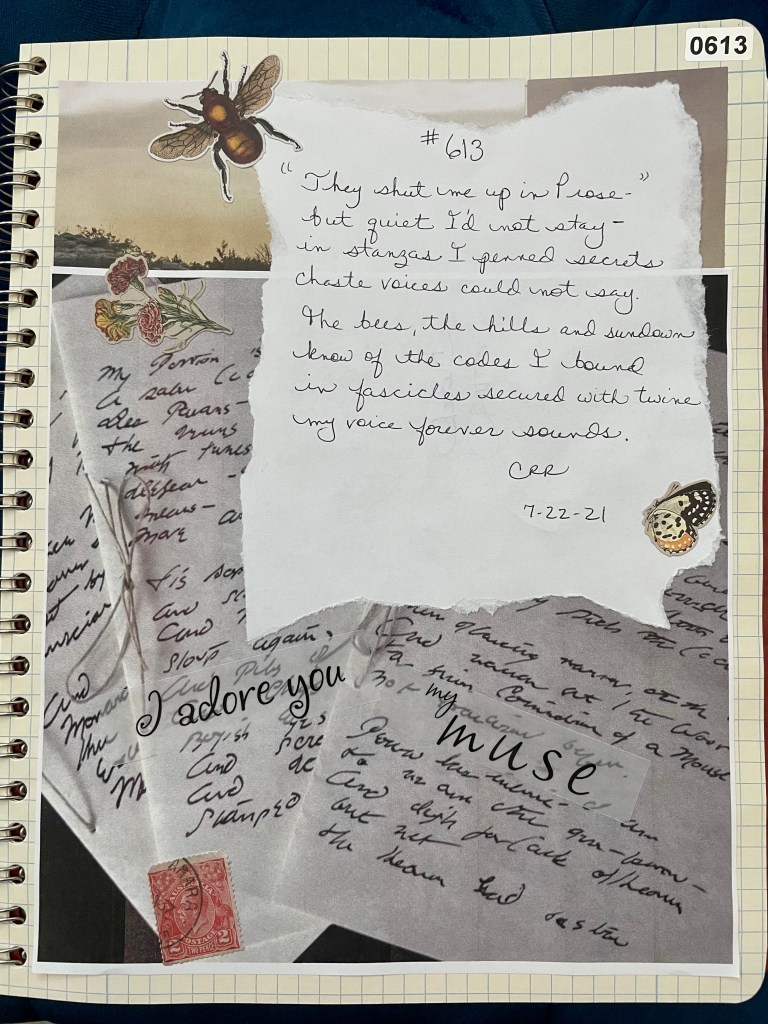

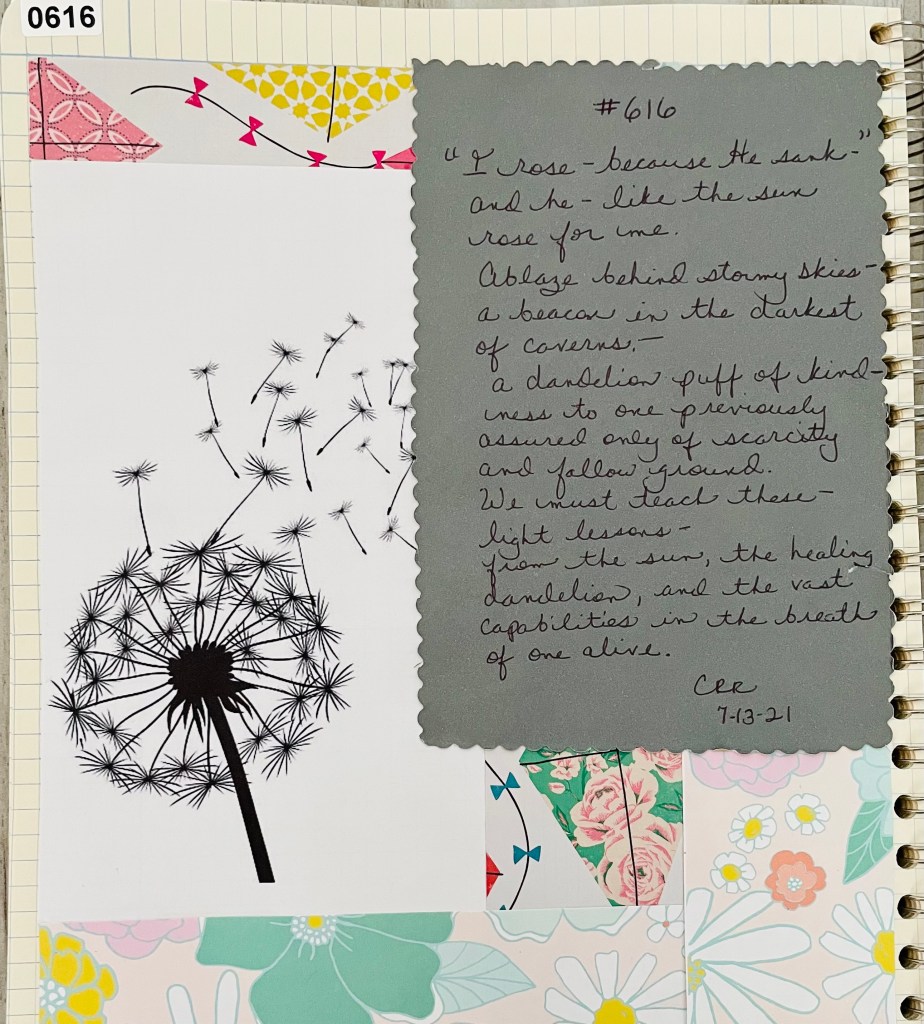

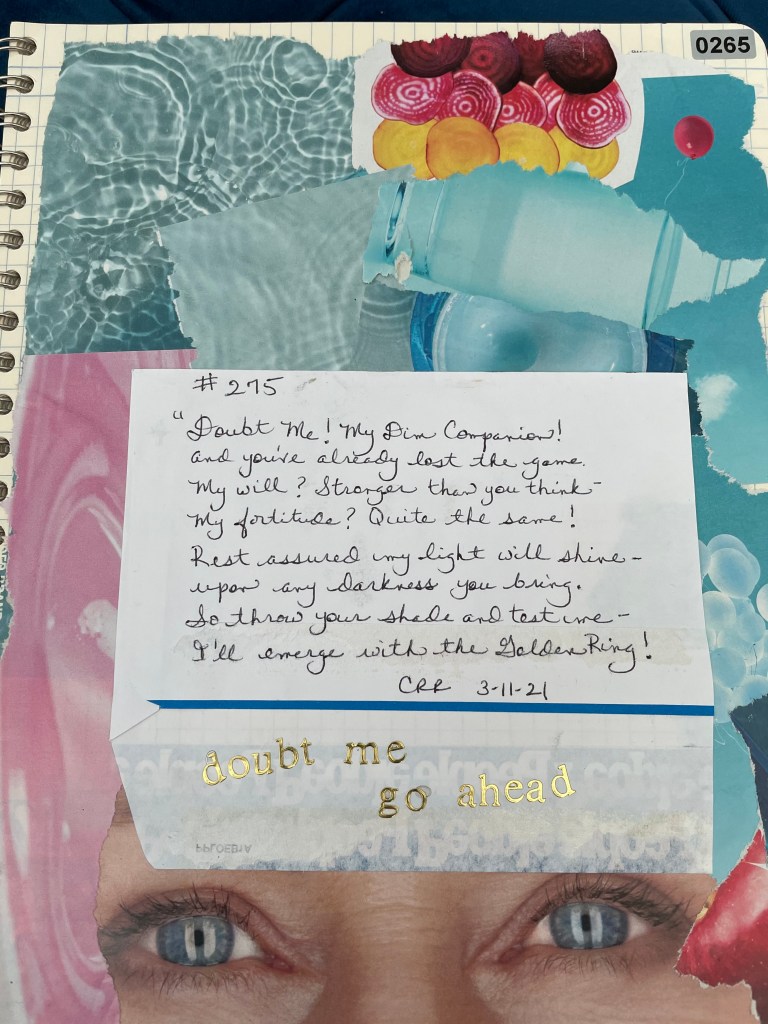

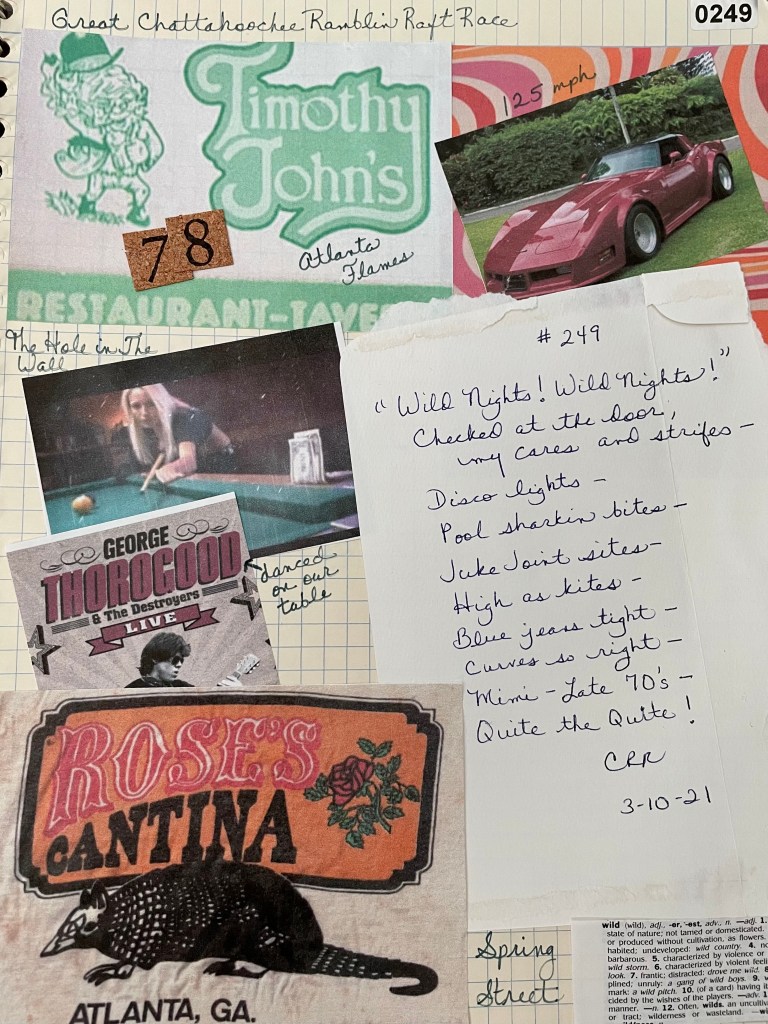

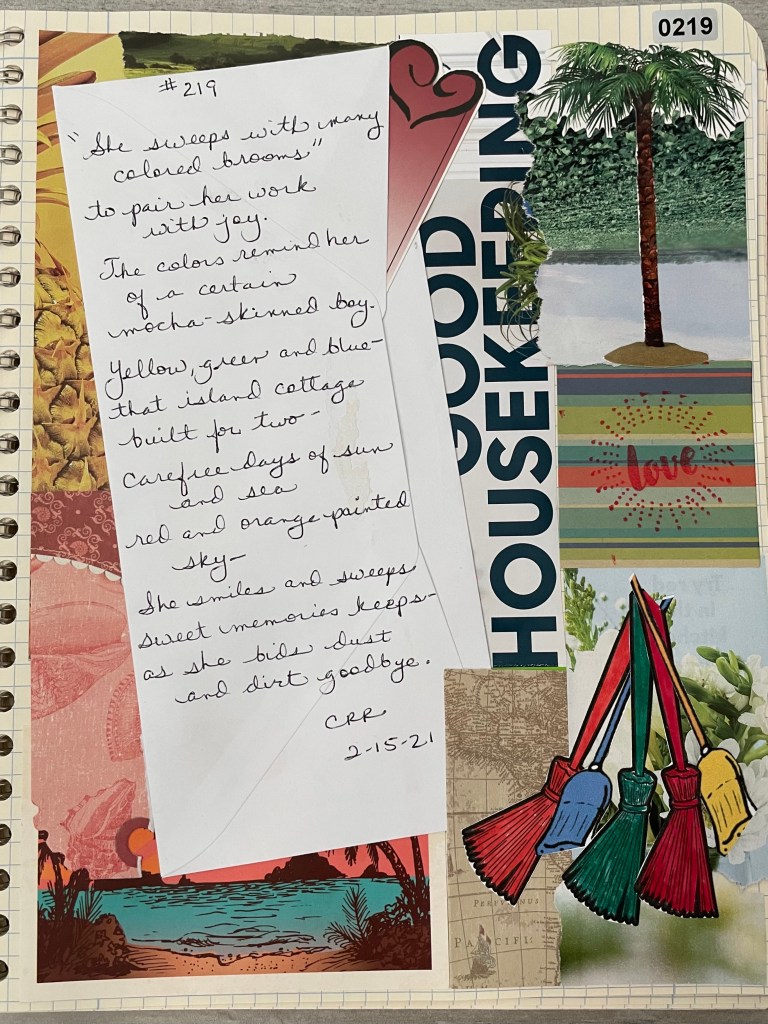

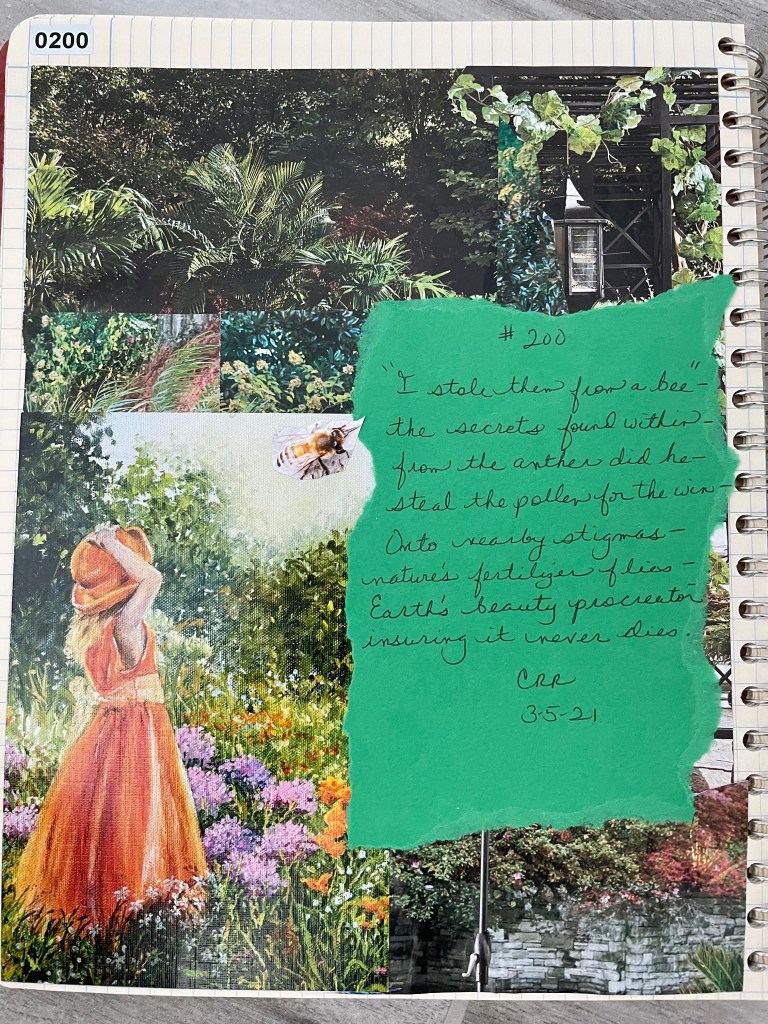

Being an admirer of Emily’s work, I thought an interesting project would be to attempt a Carol/Emily project, wherein I take the title of each of her poems and write my own, on small pieces of paper and used envelopes, just as she did. And then I remembered that Emily herself titled only a few of her 1775 poems, the others were added posthumously by editors. So much for that idea.

But what about first lines? That could be quite a challenge, given the formality of language during the 1800s, not to mention the colloquialisms of her time. But could it be a thing? I mean Dickinson on Apple TV is certainly a huge thing. I’ve binged both seasons and am suffering in wait for more.

So here we go. I mean, here I go.

New year, new challenge and all that. 1775 poems. Stay tuned. I’m sure some of it will be less than spectacular, but who knows until I try.

Emily herself said:

“Success is counted sweetest

By those who ne’er succeed

To comprehend a nectar

Requires sorest need.

Not one of all the purple Host

Who took the Flag today

Can tell the definition

So clear, of victory,

As he, defeated – dying –

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Break, agonized and clear.”

Click the arrow at the top right of this page and a pull down will appear so you can subscribe if you’d like to follow along and wish me luck!

Click the arrow below to read past posts or check out the archives by clicking on the arrow top right and then looking to the left.